South Africa has got its fair share of pioneering winemakers. Which is saying something considering it has only been making wine on the international stage for the last 30 years.

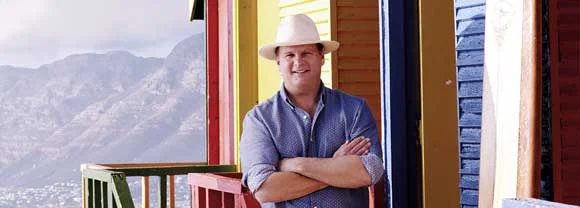

But arguably none have had the influence of Bruce Jack when it comes to bringing both mainstream and prestigious wines to the global wine consumer.

There are certainly higher profile and more outspoken winemakers in South Africa, but there are few who have consistently been at the forefront of anything new, exciting and attention grabbing coming out of the Cape.

Now we all know the saying when it comes to Jacks. But this is one Jack that has become a master of quite a few trades in his time.

He can also boast a few firsts as well.

He was, he claims, the first South African to train at Australia’s acclaimed Roseworthy Wine School at Adelaide University.

He was also one of the first winemakers not to own his own grapes or vineyards. Instead setting up a “virtual” winery and renting out vines and buying in grapes for his Flagstone Wine business.

He was also the first, he says, to make a "Cape Blend" with the Flagstone Dragon Tree 1999 where Pinotage was the hero grape variety making up 30% to 60% of the blend.

And was one of the first major independent wineries to sell out to an overseas drinks colossus - Constellation Europe at the time.

But more of that later

Wines from here, there and everywhere

To describe Jack as a South African winemaker is not strictly true. For a large part of the wine he makes every year comes from thousands of miles away across Europe, with a number of projects across Spain and France.

To do so means knowing precisely what is going on in those key markets. His knowledge, for example, of the UK wine trade is as sharp and on the button as any local supermarket buyer or wine distributor.

In fact sitting down for dinner with him at High Timber, South Africa's home from home in the heart of London, it was hard to keep up with the number of wines he is involved with. Which at a rough count covers near on 100 wines and some 20 different brands.

This covers his work at Flagstone, as chief winemaker for Accolade Wines, and his personal South African projects, The Drift Farm in Overberg in the Western Cape and Bonfire Hill where he is producing a whole range of exciting, experimental and classic wines.

Then there are all the projects outside of South Africa.

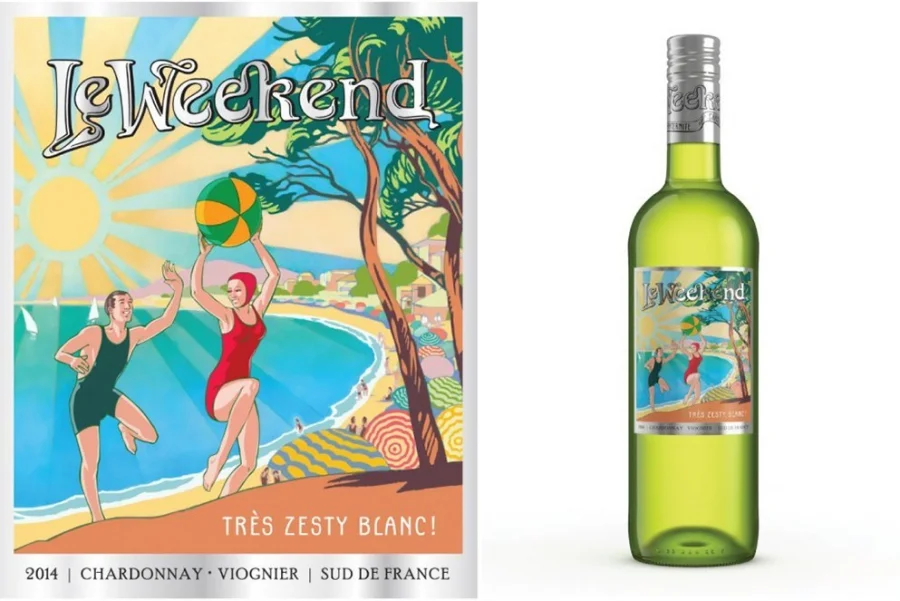

Jack has developed Le Weekend with Australian winemaker, Karen Turner, a fellow Adelaide University graduate

Projects like Le Weekend wine which he is making in the South of France at Domaine Turner Pageot, with Australian winemaker Karen Turner, one of his graduates from Adelaide University.

A wine Jack hopes might make a little crack in the US wine market with labelling evocative of the old travel posters of the 1920s and 1930s.

He is also heavily involved in developing and making Spanish wine from right across the country from his joint projects, La Báscula and Malabrista with long-term winemaking friend Ed Adams MW.

Here they make around eight different styles of wine, including the No Stone Unturned, Catalan Eagle, The Charge and Heights of the Charge.

So how does he keep so many projects up in the air at one time? Jack seems pretty unfazed.

“It is all pretty much control. I come over to Spain, for example, a couple of times a year to do the blending and see how the harvest and vintage is doing,” he explains.

Vinetrotter

It is not surprising Jack has got a wandering eye when it comes to the vineyards. Prior to studying oenology and viticulture at Adelaide he had already spent time at St Andrews University in Stirling, Scotland.

He only returned to South Africa to start making wine after he had already done so in the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale in Australia, Bordeaux and Sonoma and California, in the US.

But when he did return to South Africa it was to start up his “virtual” winery, Flagstone Winery, a business he is still enormously passionate about and involved with on a daily, if not hourly, basis.

The Flagstone brand has grown to become one of the country's most important premium brands and is, says Jack, the second fastest South African brand in the UK on-trade, and second biggest by volume.

"This was a brand I started with my father in 1998 and will always feel like one of my children. I spend a disproportionate amount of time on this brand. But the day-to-day winemaker is Gerhard Swart - he is absolutely brilliant," says Jack.

World wide view

Having so many interests outside of South Africa, and Accolade Wines, might, on paper, look a little overwhelming, but for Jack it is vitally important to help him see the wine trade from all sides.

It also means he gets the chance to see how other big corporate wine distributors and companies work compared to Accolade Wines.

All his Spanish wines, for example, are handled and distributed by Boutinot in the UK, whilst Matthew Clark and Tesco online have some of his other wines including its Dragon Tree label and his Drift Farm wines are mainly handled by Alliance Wine.

It is not surprising, therefore that the UK is very close to Jack’s thoughts. “It is the market I understand the most,” he admits. “But it is also still the most important wine market in the world. If you can sell wine in the UK you can sell it anywhere.”

But, he believes, it is vital for any winemaker to be out in the field where their wines are being sold.

“It is important you are in the market as much as possible. Talking and listening to people. It is not just about Nielsen data. The best thing to do is to walk down a supermarket aisle or stand at a bar and watch people how they buy wine. That will show you what is really going on. You have to get out of the winery,” he adds.

It is also why he likes to do so much wine judging as it allows you to see so many different styles of wine that consumers are drinking.

His work means he is also visiting, and tasting, on a regular basis wines in New Zealand, Australia, Chile and America.

What it all means

Which is at the heart of Jack’s winemaking philosophy.

“You have to look back to be able to look in to the future. You have to understand the complexities of the Old World and then take on board what the New World has done in terms of opening up people to literally a new world of wine.”

But we can’t look at wine in isolation, stresses Jack.

“You have to understand the whole drinks category rather than look at wine as being in its own category. We have to think of wine as a drink, it is an option just like an RTD, a pint of cider, a vodka tonic,” he adds.

“You can’t be so arrogant to make a wine and say that is the style. You have to make it drinkable. You have got to adapt it so that consumers are going to like it,” he explains.

It is not hard to see why Constellation came calling on Jack when it was looking for a wine partner in South Africa. He is the rare winemaker who sees his world through the eyes of the consumer and sets out to make wines they want to drink and buy.

Upside down

Bruce Jack and his winemaking family at the Flagstone Winery

But when news broke in the autumn of 2007 that Jack was prepared to throw his chips in with Constellation, the then biggest wine company in the world, there was many an eyebrow raised not only amongst his fellow South African winemakers, but this side of the wine world.

But eight years down the line it is clear Jack has no regrets and, in fact, believes it has allowed him to not only produce better quality mainstream wines, but given him the capacity and freedom to develop so many other projects, like acquire The Drift Farm.

It has also unquestionably helped the scale, profile and ultimately the performance of South African wine in general to have one of the world’s wine superpowers, in first Constellation and now Accolade Wines, committed to making and developing winemaking in your country.

Part of Jack’s initial, and ongoing job, is to over see the style and future of South Africa’s pivotal Kumala brand, which was once responsible for nearly a quarter of South Africa’s export sales, and other key South African brands such as Fish Hoek and, of course, Flagstone.

The fact Jack is there pulling the winemaking strings has certainly helped Accolade find its feet in the Cape.

It is still a careful balance, but with Paul Schaafsma at the helm of Accolade, Jack believes he could not have a better corporate partner to work with.

Jack: Paul Schaafsma, Accolade Wines's chief executive, gives winemakers freedom to make quality wine

“Paul is genuinely so aware of the role winemakers play. He just tells us to get on with our jobs and make the best possible wine possible. It is incredibly refreshing and liberating in such a big business,” says Jack.

“We are a wine business and the focus is very much on allowing the winemakers to take it to the next level. That is the ambition that Paul gives us,” he adds. “As a result we are doing so much exciting stuff."

It is an approach that clearly resonates with Jack. "Winemakers need to be part of the strategy of any big wine business, otherwise it lacks soul and is unsustainable," he stresses.

It is also reflected in the number of winemaking awards that Accolade wins.

But he is also quick to point out that clearly there are some wines in the Accolade portfolio which have to hit certain price points and absorb costs. But never at the expense of the overall quality of the wine, he stresses.

He also fully appreciates how lucky he is to have the flexibility and freedom to be able to go out and make his own wines outside of Accolade. Not all private equity backed businesses might be so accommodating.

Jack explains how it works: "It's all about ensuring there is no conflict with Flagstone, in particular, and that suits me fine, as I am like one of those really irritating, over-protective parents, who can't quite let go, even though your child has grown up!"

It essentially means that for most of the year 70% of his time is spent with Accolade, which can stretch to 100% during key periods, and the rest he is free to explore his own projects.

A good corporate, life work balance.

Long term view

With so much on his plate it perhaps makes sense for Jack to find comfort by looking in to the far future. “Many of the wines I make will last and grow for the next 20 years,” he says.

As he talks through his portfolio of Drift Farm wines, which includes a single vineyard rosé, Pinot Noir and Barbera and his classic blended red wine, Moveable Feast, Jack shares his inspiration for the type of wines he wants to make. Particularly the reds.

He recalls travelling through the Rhône with his wife in the 1990s and stopping next to a vineyard with a type of old vines he had not seen before. He did not know it at the time but he was in Gigondas.

When he went on to taste the wines he was taken back by the “persistent, more-ish tannins”.

“I said then that was my goal to make wines with the same more-ish appeal,” he says.

It is a philosophy he takes in to every wine he makes. Be it a mainstream, promotion driven wine for the supermarket, or an award winning, benchmark wine at the higher end of the wine spectrum.

“The only danger comes if you lose focus that your job is to make really good wine,” he stresses.

In Bruce Jack’s world, there is little chance of that.